Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

First introduced in the 1999 edition of the National Electric Code, AFCIs were required for bedroom receptacle outlets, and in every code cycle since their introduction, the protection requirements have expanded.

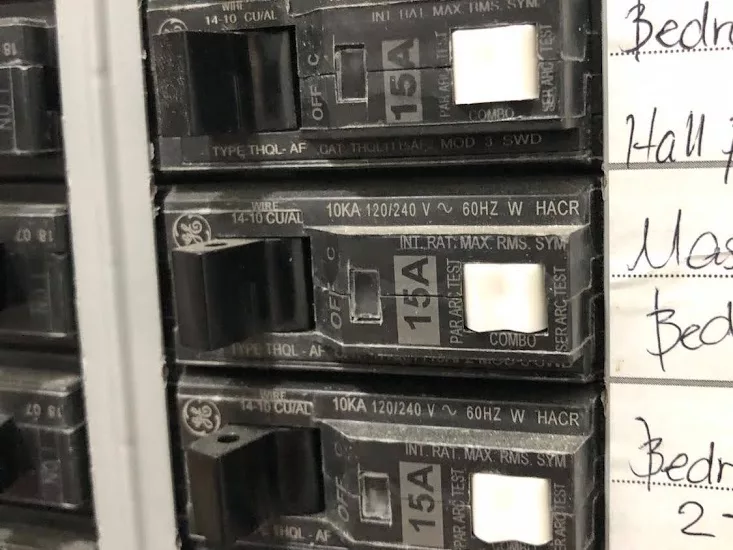

Today, AFCI breakers are required in almost all locations in the building. Here’s a look back at the evolution of arc-fault requirements.

1980 – CPSC sponsored a project to identify the rising causes of home fires.

Late 1980s & Early 1990s – Appliance manufacturers became concerned about power cord damage leading to home fires and the uptick in TV, VCR, and stereo fires. The national electric code proposed changing the instantaneous trip level of molded case circuit breakers (MCCB) to 85 Amp. The proposal was rejected because lowering the instantaneous trip level of MCCBs would result in unwanted (i.e., nuisance) tripping due to inrush currents.

1992 – Underwriters Laboratory (UL) created a study on lowering the instantaneous trip level of MCCBs.

1993 – The consumer product safety commission (CPSC) created a task force to address home wiring fires. It was called the “Home Electrical System Fires Project Task Force.” This turned into a three-year project that addressed the deterioration of electrical distribution systems due to aging, overloading, or incorrect modification.

1994 – The National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) formed a task force on AFCI circuit breakers, and that same year, UL approved and began an investigation of potential fire mitigation technologies.

1995 – UL published the findings of its fire mitigation project, and that same year NEMA requested UL to conduct a research investigation.

1996 – The UL research report on AFCI circuit breakers was issued. A proposal for AFCI protection was submitted to the National Electrical Code (NEC) by EIA, Square D (now Schneider Electric), and Cutler-Hammer (now Eaton Corporation). The proposal was accepted.

1997 – The first commercial AFCI circuit breaker was introduced.

1999 – Bedroom receptacle outlets only (effective date of Jan. 1, 2002)

2002 – Expansion to all dwelling unit bedroom outlets, including those for lights and fans (not just receptacle outlets). That code cycle also confirmed that AFCIs must protect the entire branch circuit.

2005 – Combination-type AFCI to replace B/F type AFCI (effective January 1, 2008). It also added an exception for using OBC AFCI – – if the home run is installed in no more than 6 ft of metal raceway or a cable with a metallic sheath.

2008 – This code cycle expanded the use of the AFCI to family rooms, dining rooms, living rooms, parlors, libraries, dens, bedrooms, sunrooms, recreation rooms, closets, hallways, or similar rooms and added an exception for using RMC, IMC, EMT, or Type AC cable to protect the home run with no length restriction and the exception for fire alarm if the branch circuit is RMC, IMC, EMT, or Type AC.

2011 – This year, the NEC included an exception for the use of 2-in. concrete encasements for protection of the home run with no length restriction, and MC cable was added to the fire alarm exception.

2014 – AFCI rules for this code cycle were:

- Expansion to dwelling unit kitchens, laundry areas, and devices in protected areas.

- Expansion to dormitory unit bedrooms, living rooms, hallways, closets, and similar rooms.

- Added three new ways to meet the requirements.

- Exceptions were moved to positive text.

- Length restriction to the home run was added.

2017 – Saw an expansion to dormitory units, bathrooms, and devices in protected areas and an expansion to guest rooms & guest suites.

2020 – Expanded AFCI requirements to patient sleeping rooms in nursing homes and limited-care facilities.

2023 – This is the year the NEC reorganized the code to include all AFCI means of protection in 210.12(A) and put the protected locations in a list form, and expanded AFCI protection to 10 A branch circuits. This code cycle also expanded areas designed exclusively as sleeping quarters in fire stations, police stations, ambulance stations, rescue stations, ranger stations, and similar locations.

WHAT CAN CAUSE AN AFCI TO TRIP?

AFCI devices contain electronic components that constantly monitor a circuit for “normal” and “dangerous” arcing conditions. The following shortlist is considered good arcing (operational arcs). We want to distinguish them from bad arcs (hazardous arcs). Good arcs are created from the normal operation of the device. Good arcs can happen when:

- When you run your vacuum.

- When you operate a hair dryer.

- When you use an iron or another thermostat-controlled device.

- When you operate a lighting dimmer switch.

- When you set up the treadmill and plug it into an AFCI-protected circuit.

Bad arcs. Unfortunately, the list of bad arcs is longer than it should be and is the primary reason an AFCI device should be installed. Here are some examples:

- An overloaded circuit. Example: you have too many devices plugged into a receptacle.

- You can’t see it, but you have faulty wiring. You want an AFCI to protect you.

- You want to dim the light in the room, and you unscrew a light bulb – that can become a bad arc and can trip your AFCI.

- The loose receptacle or wall switch you meant to tighten is now creating a bad arc. (this one is common)

- A doorway or heavy furniture pinched your extension cord and is damaged, creating a bad arc.

- Most often found in the attic, animals and vermin (raccoons, rats, mice) chewing through wiring insulation.

- As wires age, the sheathing may become brittle, crack, and lead to a tripped AFCI breaker.

- A power surge or nearby lightning strike has damaged your wiring and is causing a bad arc. (you surely want this one detected by an AFCI device)

- This list goes on and on and on…

DIAGNOSE YOUR AFCI BREAKER

If your AFCI breaker trips, find your electric panel and note the specific circuit the breaker is protecting. Read the label (e.g., kitchen, bedroom, living room, lighting, etc.), and while the circuit breaker is in an ‘OFF’ state, confirm that there are no obvious issues with the loads on that circuit, follow these steps:

- Check for any blackened plugs or outlets. You should NOT see soot on your outlets, switch covers, or surrounding surfaces. If found, remove all plugs from the outlet and contact an electrical contractor for further investigation right away.

- If there are lights on the circuit (for example, bedroom lights), check for loose connections between the light bulbs and sockets. Tighten the bulb if needed – or remove the lamp altogether.

- Check for any damage or crimps in all electrical cords plugged into an outlet on the circuit. Possible conditions contributing to cord damage:

- a. Cords are pinched in doorways.

- b. An appliance or furniture is pushed against an electrical plug or resting on a cord.

- c. Cords deteriorated due to proximity to a heat source (heaters, hot air ducts, sunlight, etc.).

- Ensure all bulbs are less than or equal to the maximum wattage rating of the fixture. Higher-rated bulbs can cause excessive heat and damage, leading to a tripped AFCI.

- Unplug all equipment on the affected circuit (for example, hair dryers, radios, clocks, etc.)

- Reset the circuit breaker by actuating its handle to the ‘OFF’ and then ‘ON’ position. If the circuit breaker trips again, a fault still exists. Observe and record the trip indicator LED lights. Call an electrical contractor to investigate the issue.

- If the circuit breaker does not trip after all equipment has been unplugged, follow these steps:

- a. Turn on and off each light individually if lights are on the circuit, and observe if the circuit breaker trips.

- b. Plug in non-defective equipment one at a time, turn it on and off, and observe if the circuit breaker trips.

- If the circuit breaker trips, remove the equipment or light that caused a trip event from the circuit before reenergizing the circuit again and call an electrical contractor. Ask if they use this diagnostic tool.

The main takeaway is that AFCIs were developed in response to an identified electrical problem causing fires in the home, as noted by the Consumer Product Safety Commission and other prominent organizations. An AFCI breaker provides a higher level of protection than a standard circuit breaker by detecting and removing the hazardous arcing condition before it becomes a fire hazard.

If you’re considering purchasing an older home, I highly recommend protecting yourself by adding AFCI breakers to your electrical system. If your local code authority doesn’t require the device, you should have it installed on all 15 and 20A branch circuits, not just those in bedrooms.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -